Brighton’s St Nicholas of Myra, a ‘Victorian’ medieval

parish church.

knights who owed fealty (services and loyalty in return for their land) to William de Warenne their Lord, a loyal supporter of King William Ist (William the Conqueror).

In 1090, Ralph, with the approval of William de Warenne II gave the church to Lewes Priory with the tithes (a tax on land to support the church) he received from people on his land in Brighton, as a source of income. Several knights gifted churches with income to help support the Priory.

|

| Map showing the old parish of Brighton and those which surrounded it. In 1873 the old parish was divided |

Lewes Priory (which was founded by the de Warenne

family) embellished its churches with wall paintings and sculpture mainly in

the Romanesque style in the C12th and C13th centuries and experts believe that

the font dates from this period and has been in the church since then. The

monks probably had the church walls frescoed as at Clayton which they also

owned. The Priory’s mother house was at

Cluny in France and so the monks were probably well informed about the latest

fashions in church decoration.

When Lewes Priory was closed, its records were lost

and so we have little information about St Nicholas from the medieval

period.

|

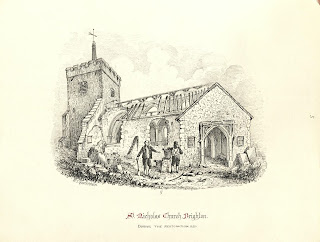

| St Nicholas Church by Petrie c1800, one of the earliest clear images |

The surviving medieval fabric is

mainly from the C14th and consists of the arcades in the nave and the chancel

and tower arches. So, the church was one of many which were altered or almost

rebuilt during this period, probably to suit changes in worship and perhaps to

accommodate a growing population. Little was done to many churches after the

severe outbreak of plague (also called The Black Death) in the 1340s which

reduced England’s population.

The early Tudor church was still decorated, in 1531, J

Fychas left a legacy for gilding the rood screen but we don’t know whether the

screen referred to is the one in place today which is thought to have come from

Norfolk because of its style. Given the changes to the church because of the

Tudor Reformation, the removal of an old screen was possible – it happened

elsewhere to eradicate reminders of the Roman Catholic faith from churches.

Frescos were whitewashed for the same reason.

|

| Earp, a local artist did this in the 1840s Owned by the Sussex Arch Soc. |

By 1724 the church had altered a lot because of the sermon- based service which had become the accepted Protestant form of worship. We know that the churchwardens reported to the Bishop of Chichester that the church was in good repair and in the 1740s there was at least a west gallery with box pews on it and probably therefore, more in the nave.

Most of the pews in the church were built by their

users who let them and sold them. Richard Tidy had used his pew for over

half a century when he sold it to Sir Robert Bateson Harvey in 1803 with his house. This link of a pew to a house was not unusual. Harvey

sold the pew on in 1816 and described it as opposite the East Door and accessed

by a flight of external steps to the gallery. The pew measured seven feet by

five feet.

|

| Sketch by R H Nibbs 1849 showing steps giving access to the galleries. Owned by the Sussex Arch Soc |

|

| Nibbs also sketched the congested interior - note the galleries. |

Numerous prints and watercolours of the church made in

the later C18th and early C19th show the dormer windows and steps inserted into

the fabric to give access to the galleries which, by 1800 were on all sides of

the nave. But it is the sketches and prints of the interior which show the big

pulpit, the reading desk for the parish clerk and the congested look of the

building which also warrant close inspection.

People who could not afford pews had some space in which to stand in the

nave and possibly (as in the case of other churches) at the back of the

galleries.

By the 1790s, the church could not accommodate even those

who could afford pews and so a Chapel of Ease was built in North Street. Called

the Chapel Royal (much revamped in the later C19th), it was the property of the

builder, in this case the vicar of the parish and he had to earn enough from

the income from pews to pay for its upkeep and for a curate. Most of the

population could not afford to go that church either. It is unsurprising that

non-conformist chapels sprang up in Brighton from the later C17th.

|

| This view by Wooledge owned by Brighton Museum shows the west entrance in the 1840s |

Meanwhile, worship and, tastes in church design were changing. More ritual was returning to services. This change required the use of church chancels, which in many churches had been used as extra space for pews because there was no need for an altar. There was a move in some churches away

from long sermons. Concern was being

expressed by some Anglicans that many people could not afford to go to church

and the lack of free pews or benches or stools made people feel unwelcome and this also put pressure on those involved with parish churches to find more more free sittings.

|

| Demolition of most of the old fabric was captured in several drawings by W G Quartermain of this is one. Owned by the Sussex Archaeological Society - see website under library for this and more |

Rev Henry Mitchell Wagner, the wealthy and energetic

vicar of the parish of Brighton decided that the growing town needed more Anglican churches and took the lead in the building some within the parish. In 1833, the Wagner family contributed towards the cost of two in the classical style popular until the 1830s. The first was All Souls, Eastern Road (demolished) and the second. St John the Evangelist on Carlton Hill in 1840 (now owned by the Greek Orthodox Community).

Henry Wagner's taste in style then changed, possibly due to the influence of Arthur, one of his sons who became well known for his Anglo-Catholic churches. Henry commissioned the fashionable R C Carpenter to design St Paul's in West Street in 1846/7. This distinctive church survives. Carpenter also designed All Saints in Compton Avenue opened in 1852 (demolished).

Henry Wagner's taste in style then changed, possibly due to the influence of Arthur, one of his sons who became well known for his Anglo-Catholic churches. Henry commissioned the fashionable R C Carpenter to design St Paul's in West Street in 1846/7. This distinctive church survives. Carpenter also designed All Saints in Compton Avenue opened in 1852 (demolished).

|

| View towards the surviving arcades from the chancel |

Henry Wagner also wanted to rebuild St Nicholas and in 1846 also asked Carpenter to provide the estimates and design. It was still to be a

Gothic church in appearance but without the box pews, dormer windows and stairways and, with

wider aisles and some free sittings. The internal re-ordering replaced box pews with the long bench pews which are now in their turn being taken out of churches as in the example of this church.

Wagner's idea had to wait because in 1846 residents of the

parish who were eligible to pay rates towards the care of the town also had

to pay church rate to maintain St Nicholas. At a meeting, they rejected Carpenter’s £4305

estimate.

Ratepayers who did accept that

the church must be maintained preferred the far cheaper suggestions of the very

competent Borough Surveyor, George Maynard. He estimated that cleaning the

building up and re-roofing a bit of it would cost £278 and other work a bit

more. Church rate was not legally

enforceable although churchwardens and vicars tried hard to collect it. Non-conformists

felt that they should not pay as they did not attend the church and, because

the government helped to subsidise church building for the Anglican Church –

one heavily subsidised local example was St Peters built 1824-28 by the vestry

as a chapel of ease for St Nicholas.

This church was expensive, few big churches erected after 1830 cost £26,000.

This is a photograph owned by Brighton Museum of Henry in his later years.

|

| This image from the Brightonian is of his son, Arthur Wagner who became well-known for his support of Anglo-Catholicism. |

When the Duke of Wellington who had spent a short

period of his boyhood in Brighton died in September 1852, the transformation of

the church was promoted as a memorial to him by Henry Wagner. The funds were

raised and a faculty (permit) sought from the diocese to rebuild the church. Carpenter was asked not to exceed £4,600 for

the work and to submit the documents needed for tenders the church building

committee. The balance of the £4,834 was kept as a reserve. All work on the church had to be bid for and, the

tenders published, both normal for church building with public money from

the 1830s.

|

| The Wellington Memorial |

Robert Bushby won the rebuilding contract because his

was the lowest tender at £2,985 demolish and rebuild. This is when the medieval church

was stripped down.

Wellington memorial designed by Carpenter was sculpted

by John Phillip and ready in 1854. Modelled on Eleanor Crosses, it attracted

small children whose desire to climb on it resulted in an iron fence being

erected.

When the old church was demolished leaving the arcades

and arches as shown in the drawing by Quartermain, memorials had to be kept

which explains why the two memorials by Westmacott have survived. The builders also retrieved three old large

pieces of lead from the roof which are now carefully stored and looked after

because they have dates on them of roof restorations and the names of those

involved.

Carpenter died in 1855 shortly after the completion of the church, aged only 43, but by then the church was being criticised because it was dark inside due to the lack of clerestory windows high up just below the roof line which it has today. This issue was not addressed until the 1890s as we shall see.

Carpenter died in 1855 shortly after the completion of the church, aged only 43, but by then the church was being criticised because it was dark inside due to the lack of clerestory windows high up just below the roof line which it has today. This issue was not addressed until the 1890s as we shall see.

Until 1873, when St Nicholas ceased to be the parish

church for the entire ancient parish, then other church of England churches and

chapels within the ancient parish were daughter churches and chapels of ease.

In 1873, the parish was subdivided. St Peter’s became the ‘main’ parish church

and the parish records and the administrative functions were transferred from

St Nicholas and, many of the former chapels of ease within the old parish became

parish churches. The registers of baptisms, marriages and burials reflect the

changing standing of St Nicholas. Before 1873 the registers of St Nicholas

included entries of events at the daughter churches and chapels which the

clergy sent to St Nicholas for record. This change explains why St Peter’s was

enlarged in the late 1800s.

The next major phase of work on the church was during

the 1870s. Again, most of it was paid for by public subscription.

|

| Section of ceiling by Kempe after restoration |

In 1876, The beam above the rood loft, the cross and the

bronze gates for the rood screen were a

memorial gift, given by Alderman Bridgen, in memory of his wife Mary, The

designs were by C. E. Kempe. Charles Lynn, a church warden, paid for new

stone sanctuary steps.

|

| Rood loft, chancel side. |

In 1877-78 Somers Clarke worked with George Lynn the

builder on the large new choir vestry and the cloister link to Church Road,

both of which survive. An oak sedilia was added to the south side of the

chancel wall with the intention of extending it right round when funds allowed,

but meanwhile a debt of £200 had to be paid off.

Then, from 1879 the new scheme for stained glass

windows by C E Kempe began, the costs of each paid for by subscribers. Eight of the eighteen windows were completed

by 1880 and the costs of two more windows promised which left the remaining

eight to do. The Vicar of Midhurst (formerly a curate at Brighton) donated the

reredos for which three oils were commissioned from M R Corbett and the

lighting improved.

‘Superior tiling’ was laid in the chancel and the

tiles in the vestry replaced with an oak floor to make it quieter and warmer

and five more of the Kempe windows completed. The lighting was improved with

gas chandeliers.

Although the precise evidence is still being hunted for,

Kemp’s involvement suggests that he also designed and painted the walls and the ceilings

of the nave and the ceiling of the chancel, to compliment the

windows. The east and west walls are thought to have been painted in

1890-92. Again, work would only have

proceeded when funds had been raised.

During the 1880s, the cross in the churchyard, south of the church porch was donated in memory of Dr George Hilders, a celebrated homoeopathic doctor.

In 1892-3 the roof was raised, to, the instructions to the carpenter and joiner were brief and succinct…’the existing roof to be lifted bodily’.... which preserved Carpenter’s roof. Somers Clarke and Michlethwaite the architects instructed that a wall of brick in cement with a flint facing be inserted between the twelve stained glass clerestory windows by Powell. This is what we see today.

During the 1880s, the cross in the churchyard, south of the church porch was donated in memory of Dr George Hilders, a celebrated homoeopathic doctor.

In 1892-3 the roof was raised, to, the instructions to the carpenter and joiner were brief and succinct…’the existing roof to be lifted bodily’.... which preserved Carpenter’s roof. Somers Clarke and Michlethwaite the architects instructed that a wall of brick in cement with a flint facing be inserted between the twelve stained glass clerestory windows by Powell. This is what we see today.

In 1893 a lectern was designed by Somers Clarke to

match the ‘lofty pulpit’ on the north side of the church arch and made by ‘Mr

Knox of Kennington Cross’.

|

| The south chapel widened in 1900 |

In 1900 Michlethwaite widened the south chapel.

In 1917, Barkentin and Krall produced (and maybe

designed the figures) on the rood screen on which more information is sought.

Fund raising for the care of the church continues and

in 2001 the church was re-ordered. The long fixed Victorian bench pews were

replaced with chairs so more events can be hosted. The font and Wellington Memorials were moved

to their present sites. New flooring, heating and lights installed. Since then, £115,000 has been raised and spent

on restoring the east wall of the nave, the ceiling above, the screen and the

west wall of the nave.

There

are many local links between the church and the City – Somers Clarke was a

local man whose practice was in London. Charles Eamer Kempe was born in Ovingdean. His father

was Nathaniel Kemp who built Ovingdean Hall. The Kemps sold Ovingdean Hall and

moved away whilst Charles was young. He added the ‘e’ to Kemp. Eamer was his

mother’s surname.

A copy with the sources is revised as more information appears/ corrections are needed and this blog will be updated. This was last updated on Sunday 16th Sept 2018.